Pediatric Obesity – Global Perspective

- Worldwide one in 10 children (aged 5-17 years) is overweight, a total of 155 million, of which around 30-45 million are obese.1 The obesity rates are nearly double (18%) among teens (aged 12 to 19).1

- Countries with the highest prevalence of overweight are located mainly in the Middle East, North Africa, and Latin America.2, 3

- In the United States, the prevalence of childhood overweight tripled between 1980 and 2000.4 Almost one-third of US children over 2 years of age are overweight or obese and as high as 39% among low-income children.5 Similar increases have been reported from Europe and Australia.2, 6In India, the prevalence of obesity in urban children is 24% ─ just under the US rate.7

- There has been a steady increase in the worldwide prevalence of preschooler overweight and obesity and has reached 7% or 43 million in 2010. This is expected to reach 9% or 60 million, by 2020.2 The prevalence of preschooler obesity is similar in Africa but lower in Asia. The prevalence of obesity is higher in developed countries (12%) and lower in “developing” countries (6%).2

- Even in the context of rising obesity rates in childhood, there is a substantial change in the weight status between adolescence and young adulthood. The prevalence of overweight status (BMI ≥25) increased by 65% between mid-adolescence and the age of 24 years, and the prevalence of obesity (BMI ≥30) has almost doubled.8

- Even in the context of rising obesity rates in childhood, there is a substantial change in the weight status between adolescence and young adulthood. The prevalence of overweight status (BMI ≥25) increased by 65% between mid-adolescence and the age of 24 years, and the prevalence of obesity (BMI ≥30) has almost doubled.8

- These alarming statistics underscore the need for early intervention at a very young age. Given that the trend toward childhood obesity starts as early as age six months, the infant and preschool years are considered possible critical periods for such interventions and programs. Waiting for school programs to address this problem is probably too late.2

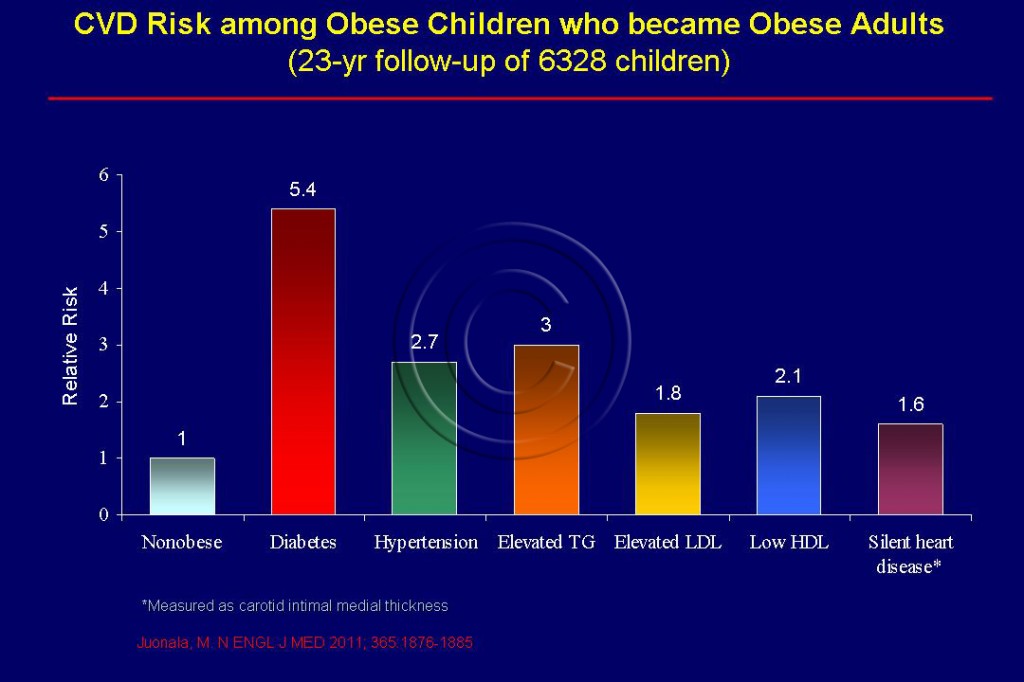

- Obesity is the principal driver of childhood metabolic syndrome which predicts clinical CVD in adult subjects at 30- to 48-years of age.9

Diagnosis

- A child is considered to have elevated waist circumference if the waist girth exceeds 50% of the height.10 Waist to height ratio >0.5 not only detects central obesity and related adverse cardiometabolic risk among children who must be targeted for intensive lifestyle modification.11

Dangers of Pediatric Obesity

- The presence of obesity in childhood and adolescence is associated with increased evidence of atherosclerosis at autopsy and of subclinical measures of atherosclerosis on vascular imaging.

- Children are now having health problems that were previously seen only in adults – like heart disease, diabetes and high blood pressure. Too many of our children are on the fast track to a premature death.The dramatic worldwide rise in childhood obesity portends an epidemic of premature CVD in the coming decades.12

- Pediatric obesity can lead to metabolic syndrome, diabetes, hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea, dyslipidemia all of which can lead to premature CVD.See Figure 110.

- Pediatric metabolic syndrome is a precursor for CVD and elevated waist circumference in childhood appears to be the strongest predictors of metabolic syndrome.13 Normal weight children and adolescents rarely, if ever, have metabolic syndrome.13

- Overweight children run the risk of developing diabetes, a risk factor for CVD in young adulthood.14 Developing nations, especially India are seeing sharp rises in the number of children with diabetes (Type 2) due to changes in lifestyle.

- Compared to non-obese children, obese children are at a 3-fold higher risk for raised blood pressure ─ a major CVD risk factor.15 Obesity is linked to stiffening and clogging of the arteries, known as atherosclerosis, which is an important risk factor for the development of heart disease and stroke.15 Stiffness in blood vessels can be seen even in young children who are obese.

- Obese children have high risk of obstructive sleep apnea ─ episodes of stopped breathing during sleep ─ an emerging significant risk factor in CVD.16

- Obese teens are 16 times more likely to become severely obese adults (BMI>40), especially the girls.17

Adolescent obesity

- There is a the high rate of incident overweight and obesity between adolescence and young adulthood, 8

- Contrary to common belief, during puberty, increase in waist-height ratio ─ a simple measure of %BF is abnormal in females and even more so in males and may suggest an increased risk for adiposity-associated morbidity.18

- Substantial shifts in overweight and obesity occur between adolescence and young adulthood; There is 50% increase of overweight from 20% to 33% and a doubling of obesity 4% 7% . The he extent of continuity depends on both the severity and persistence of adiposity in adolescence. Few adolescents who peak into obesity or are persistently overweight achieve a normal weight in young adulthood. Resolution is more common in those who are less persistently overweight as teenagers, suggesting scope for lifestyle interventions in this subgroup.8

- An elevated BMI in adolescence–one that is well within the range currently considered to be normal–constitutes a substantial risk factor for obesity-related disorders in midlife. Although the risk of diabetes is mainly associated with increased BMI close to the time of diagnosis, the risk of coronary heart disease is associated with an elevated BMI both in adolescence and in adulthood, supporting the hypothesis that the processes causing incident coronary artery disease, particularly atherosclerosis, are more gradual than those resulting in incident diabetes.19

- The investigators concluded that an elevated BMI in adolescence, including one that is well within the range currently considered to be normal, constitutes a significant risk factor for obesity-related disorders in midlife. Although the risk of diabetes is mainly associated with increased BMI close to the time of diagnosis, the risk of CHD is associated with an elevated BMI both in adolescence and in adulthood, supporting the hypothesis that the processes causing incident CHD, particularly atherosclerosis, are more gradual than those resulting in incident diabetes. 19

Causes of pediatric obesity

- Many factors have combined to fuel the obesity epidemic in children such as increased consumption of energy-dense food, decreasing physical activity and the increasingly easy accessibility of food. 20

- Worldwide the urbanization of society is reducing children’s physical activity opportunities.14 Increasing calorie consumption is not matched by increased levels of physical activity in children; in fact, children globally are becoming more physically inactive.21

- Schools are becoming a less and less healthy environment where children are not protected from bad diets or encouraged into physically active lifestyles.

- Because of the link between food advertising and childhood obesity authorities in the UK have banned the advertising of high fat, salt and sugar products in or around programmes made for children or that are likely to appeal to children.

Prevention and Control

- Cardiovascular disease prevention measures should begin in life. A healthy lifestyle with regular physical activity is critical for prevention of elevated BMI in childhood. Health care providers need to partner with their community to improve health in children.

- Reported activity interventions ranged from 20-60 minutes 2 to 5 times/week in children ages 3-17 years and included a wide variety of dynamic and isometric exercises.9

Sources

1. Lobstein T, Baur L, Uauy R. Obesity in children and young people: a crisis in public health. Obes Rev. May 2004;5 Suppl 1:4-104.

2. de Onis M, Blossner M, Borghi E. Global prevalence and trends of overweight and obesity among preschool children. Am J Clin Nutr. Nov 2010;92(5):1257-1264.

3. de Onis M, Blossner M. Prevalence and trends of overweight among preschool children in developing countries. Am J Clin Nutr. Oct 2000;72(4):1032-1039.

4. Ogden CL, Kuczmarski RJ, Flegal KM, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2000 growth charts for the United States: improvements to the 1977 National Center for Health Statistics version. Pediatrics. Jan 2002;109(1):45-60.

5. Wojcicki J M, Heyman MB. Let’s Move–childhood obesity prevention from pregnancy and infancy onward. N Engl J Med. Apr 22 2010;362(16):1457-1459.

6. Magarey AM, Daniels LA, Boulton TJ. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in Australian children and adolescents: reassessment of 1985 and 1995 data against new standard international definitions. Med J Aust. Jun 4 2001;174(11):561-564.

7. Bhardwaj S, Misra A, Khurana L, Gulati S, Shah P, Vikram NK. Childhood obesity in Asian Indians: a burgeoning cause of insulin resistance, diabetes and sub-clinical inflammation. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2008;17 Suppl 1:172-175.

8. Patton GC, Coffey C, Carlin JB, et al. Overweight and obesity between adolescence and young adulthood: a 10-year prospective cohort study. J Adolesc Health. Mar 2011;48(3):275-280.

9. Daniels SR. Integrated Guidelines for Cardiovascular Health and Risk Reduction in Children and Adolescents: Report from National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute.Bethesda ,http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/cvd_ped/index.htm2011.

10. Schmidt MD, Dwyer T, Magnussen CG, Venn AJ. Predictive associations between alternative measures of childhood adiposity and adult cardio-metabolic health. Int J Obes (Lond). Sep 28 2010.

11. Mokha JS, Srinivasan SR, Dasmahapatra P, et al. Utility of waist-to-height ratio in assessing the status of central obesity and related cardiometabolic risk profile among normal weight and overweight/obese children: the Bogalusa Heart Study. BMC Pediatr. 2010;10:73.

12. McCrindle BW. Will childhood obesity lead to an epidemic of premature cardiovascular disease? Evid Based Cardiovasc Med. Jun 2006;10(2):71-74.

13. Daniels S R, Arnett DK, Eckel RH, et al. Overweight in children and adolescents: pathophysiology, consequences, prevention, and treatment. Circulation. Apr 19 2005;111(15):1999-2012.

14. Hossain P, Kawar B, El Nahas M. Obesity and diabetes in the developing world–a growing challenge. N Engl J Med. Jan 18 2007;356(3):213-215.

15. Sorof J, Daniels S. Obesity hypertension in children: a problem of epidemic proportions. Hypertension. Oct 2002;40(4):441-447.

16. Amin RS, Kimball TR, Kalra M, et al. Left ventricular function in children with sleep-disordered breathing. Am J Cardiol. Mar 15 2005;95(6):801-804.

17. The NS, Suchindran C, North KE, Popkin BM, Gordon-Larsen P. Association of adolescent obesity with risk of severe obesity in adulthood. JAMA. Nov 10 2010;304(18):2042-2047.

18. Mihalopoulos NL, Holubkov R, Young P, Dai S, Labarthe DR. Expected changes in clinical measures of adiposity during puberty. J Adolesc Health. Oct 2010;47(4):360-366.

19. Tirosh A., Shai, I., Afek A, Dubnov-Raz G, et al. Adolescent BMI trajectory and risk of diabetes versus coronary disease. N Engl J Med. Apr 7 2011;364(14):1315-1325.

20. Anderson P M, Butcher KE. Childhood obesity: trends and potential causes. Future Child. Spring 2006;16(1):19-45.

21. Storlien LH, Baur LA, Kriketos AD, et al. Dietary fats and insulin action. Diabetologia. 1996;39(6):621-631.